Credit: Mobilus In Mobil

Credit: Mobilus In Mobil

This is a guest post from Jonathan Pezzi. He is a Lexington native who studied public policy issues at University College London and currently works at a local non-profit.

In my last article, I highlighted the reasons why Lexington would benefit from becoming more walkable. In this one, I will talk about the ways our city can encourage this walkability. There are many different examples throughout the country (and world) that tell us what works and what doesn’t. Here are a few small policy changes that can make a big difference.

Mix the uses

Our city is currently set up so each part of daily-life is regimented into different zones. You live in one area. You shop in another. And you drink and eat in one more. This is known as Euclidean Zoning, and it makes walking a difficult enterprise. Instead of strolling to the corner of your block for a gallon of milk, you need to get in the car and drive. Mixing the uses fixes this.

Adjusting zoning regulations would allow business like a grocery or restaurant to locate where is most convenient and walkable, not arbitrary places where they are told to go. This Euclidean Zoning mostly came about in the gloom and grit of the industrial revolution, where public health and crime in cities could hardly be controlled. That isn’t the case anymore.

Areas can have different uses. A neighborhood can be both a place to eat and a place to live. In around 2009, Minneapolis relaxed zoning regulations to encourage more diverse offerings in neighborhoods around the University of Minnesota. The city soon reaped the benefits. More people were walking and the neighborhoods saw increased investment and revitalization.

Credit: Pierre Metivier

Credit: Pierre Metivier

Put cars in their place

Cars are a terrific invention, making transportation easier and faster for many. But it’s time we stop worshipping them, and it’s far passed the day we build our entire cities around them. They have their place, and will always be a part of Lexington life, but they currently hold priority in most planning questions. That needs to stop. We widen roads, increase the number of lanes, designate one way streets, and set aside vast spaces for parking — all in the service of the car. Unlike many other parts of city-life, this is a zero-sum game.

The reality is that if you make a street easier to drive on for cars, it makes it worse for all other forms of transport, like walking or biking. Wider roads and more lanes are both more dangerous and often lead to more traffic anyway. A balance needs to be struck. Certain parts of the city, like Man O’War or New Circle, should focuses more on cars. While others, like Short Street and Limestone, should put pedestrians first. Keeping this in mind is critical going forward. Cars do not need to be King.

Getting parking right

Credit: Mhuy222

Credit: Mhuy222

You can walk around our downtown, from our entertainment district and the Fifth Third Pavilion, all the way along Broadway to Gratz Park without leaving the confines of a parking lot. Entire blocks in our downtown are expanses of asphalt and painted parking lines. That’s a terrible use of space. One parking garage of six stories could provide roughly the same amount of parking.

It goes without saying that walking in a parking lot is unpleasant. The open space and heat catching asphalt make it an uncomfortable experience. To put them in such a central location, where parks, housing, or other useful structures could be placed makes it all the more wasteful. By repurposing these open lots and utilizing our limited space, Lexington can increase its walkability, without actually impacting the amount of parking we have.

The other side to this is parking minimums. There are many parts of the city that require a minimum amount of parking spots for each new development. Some buildings require a certain amount of spaces depending on the housing units, others based on the square footage. But across the board, it’s necessary in most of our city. Often, these requirements are not flexible, nor do they take into account what the developer thinks is necessary. What happens as a result is more red tape and less infill development. Imagine Lexington has highlighted this in one of their many reform proposals. Cookie-cutter requirements are a blunt instrument, and they usually lead to wasted space and higher costs when they’re just not necessary. Adjusting these rules brings us one step closer to making our city more walkable.

Invest in better transit

For many reasons, public transport betters walkability. First and foremost, it means you aren’t required to have a car to get around if you don’t want to, making a carless life possible in a city as sprawled as Lexington. Public transport also encourages development near transport stops. People want to live near their transportation, so they can walk easily to their station. Future development around these transport points improves a city’s walkability, as it condenses life around certain focal points of transit where walking is necessary. Studies have found as much.

Photo courtesy of Lextran

Photo courtesy of Lextran

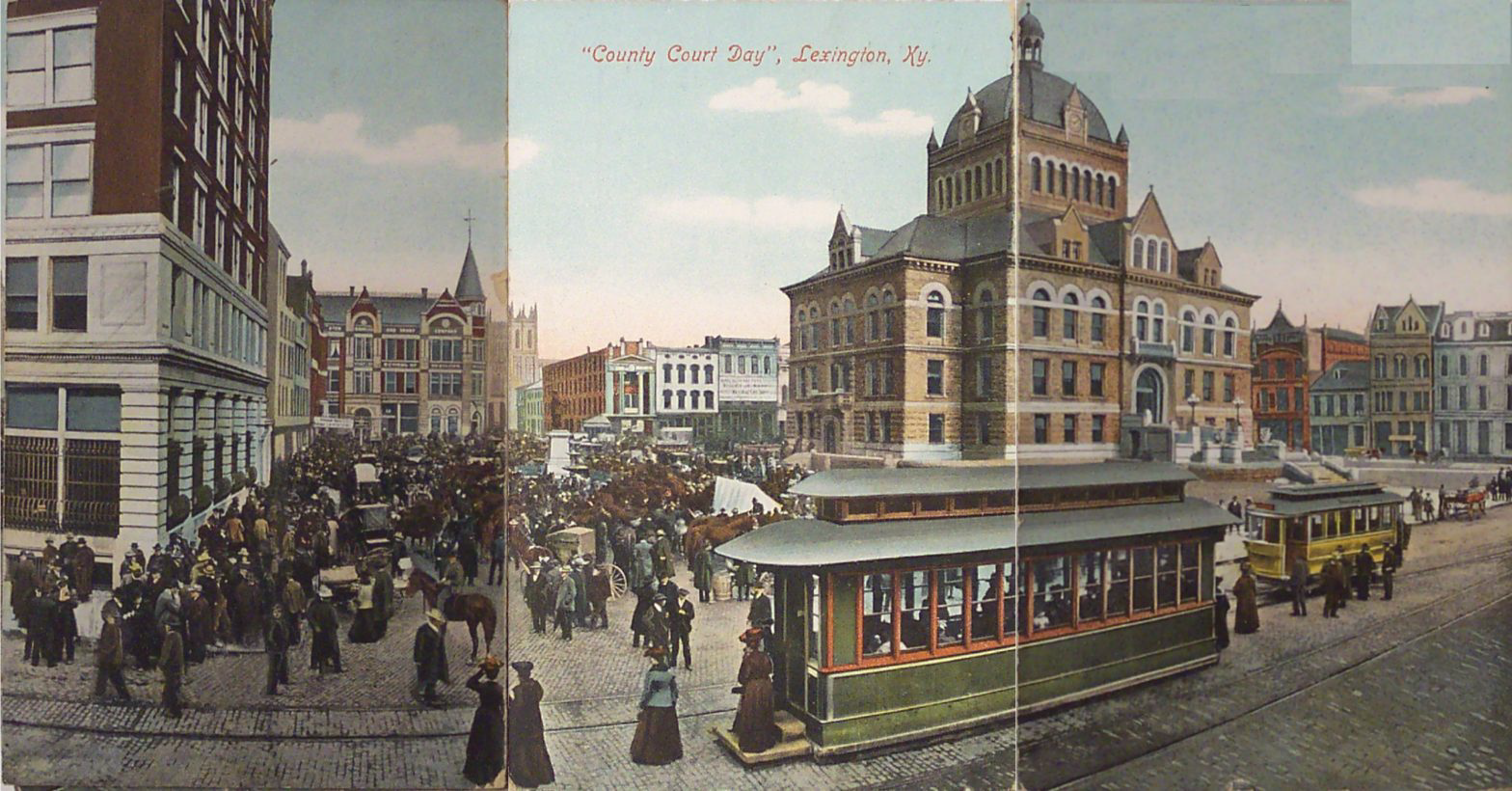

Buses are the bare minimum for public transport, and Lexington is capable of thinking much bigger. Light-rails and streetcars are more than a possibility. After all, we had them in Lexington until the 1930s. A full scale, city-wide system isn’t even necessary. Providing a line from one end of Limestone to the other, or even one from the Distillery District to Rupp Arena could be a start. Lexington could have good transit again, and it would inevitably make our city both more walkable and more equitable as well.

Some of these solutions are quick fixes, like thinking more about walkers and less about automobiles when we pave a new street or plant more trees. Others are more significant investments, like expanded public transportation. Like all problems though, there’s no one thing that will fix Lexington’s walkability problem by itself. It needs to be addressed on several fronts. Luckily, we have the answers, now we need to implement them.